- Home

- Kristjansson, Snorri

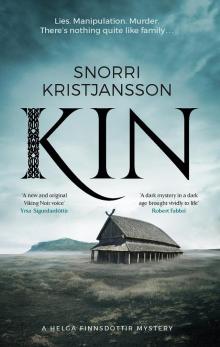

Kin (Helga Finnsdottir) Page 9

Kin (Helga Finnsdottir) Read online

Page 9

‘Karl said he’d do it,’ Bjorn replied.

Helga glanced at her mother. She’s less than pleased by this, she thought. And why was Karl in the woods in the first place? She tried to remember when she’d last seen the eldest brother.

‘Well, grab another axe and go and help him,’ Hildigunnur ordered. ‘You’re no use to us here.’

Bjorn turned without a word and left.

When the door closed, Hildigunnur sighed. ‘It’s hard to keep track of all the animals,’ she muttered.

Helga wasn’t sure she was talking about the livestock.

*

The forest echoed with the sounds of metal biting wood. Bjorn strode up the hill, axe on his back and found the clearing. His elder brother stood by a big pine, covered in sweat and grinning maniacally as he really laid into it. Two trees, each three times the size of a man, were already lying on the ground. Karl looked round, spotted Bjorn and attacked the tree with renewed vigour.

‘Greetings, Brother,’ he growled across the clearing, in between fierce axe-blows. Bjorn said nothing but walked over to the felled trees and began methodically chopping branches off. ‘Have you come to tell me how bad I am? What an honourless bastard I can be?’

The big man’s knuckles turned white around the axe-handle as he turned to face his brother.

‘Yes, I have,’ he said, cold anger in his voice. ‘You’re an arse – you always have been, but you usually only do things to hurt yourself. Why would you split up Aslak’s family?’

‘She wanted it—’

‘And even so, you would have had to want it too. You are selfish, and you break things. It’s always been that way. Now it needs to stop.’

The two brothers stood for a moment in silence, face to face, in the glade.

‘I’ve killed men, Bjorn,’ Karl said softly, ‘more than I can count. Small men. Young men.’ He rolled his shoulders and shifted his grip on the axe, eyes still trained on the giant, looking him up and down, measuring him. ‘Big men.’

Bjorn stared at his brother, lip curled in distaste – then he made a decision, turned away and set to clearing the rest of the branches.

Karl looked at the back of his brother’s head. ‘However you want it to be, my baby brother,’ he muttered, before sinking the blade of his axe back into the huge pine tree.

*

The sun was halfway down to the ground by the time they hefted the first of the trees, now hewn in half, onto their shoulders. Not a word had passed between them since they’d faced off, but the brothers had worked together often enough to need little in the way of communication. Moving briskly, they made their way between the clearing and the farmyard, chopped the trunk into logs and piled them in a neat stack by the wood shack, next to last year’s wood.

Karl moved towards the longhouse and Bjorn walked towards the smithy. They didn’t look at each other.

Breki rose to his feet, tail thumping wildly at the sight of his master.

‘Ssh, boy.’ Bjorn’s voice buzzed low. ‘Ssh.’ He scratched the dog behind the ears, finding that particular place that always turned him to mush. He gave him another scratch for good measure, starting when he realised that he was being watched: Volund was standing by the corner of the smithy, staring silently at him.

‘What do you want, boy?’

His son remained silent, and Bjorn sighed. ‘Go to the clearing up towards the new barn, Son. Fetch the axes, and as many branches as you can carry. Go on – move!’

Spurred by his father’s loud voice, Volund stumbled into action.

Bjorn watched the boy half-run, half-amble away, drew a deep breath and sighed again. ‘Should’ve drowned you when you were a babe,’ he muttered. Looking down at the dog, he pursed his lips. ‘If only he were more like you, eh?’

The wolfhound gazed up at him adoringly, tongue lolling, panting happily.

*

Helga picked her way down the hill towards the new barn. The little band of trees that she had apparently called ‘her forest’ when she was a child stretched just around the hill, that was all, but there was a delicious sound to it, she thought. Sometimes it was quiet, sometimes all rustling and bustling with life. This was one of the places where she felt most at peace. She’d jumped at the chance to get away, to sneak a little time to herself, when Hildigunnur had mentioned that she needed some tools from the box up by the new barn – she must have left her bone-handled knife up there, she’d said, and she needed it, because it was the best blade on the farm. Bjorn had offered to go, too, but Hildigunnur had told him to sit tight and sent Helga. She had a lot of things to think about: did the siblings like or hate each other? Karl snapped at everyone and everything, but was his bark worse than his bite? And was there more to Sigmar than met the eye? Despite his less-than-imposing frame he hadn’t moved an inch when Karl went for him at the games.

She was so deep in thought that when she turned a corner she almost knocked Volund over.

‘Oh – hello!’

Volund looked at her, dully at first, then there was a spark of recognition followed by the tiniest of smiles. ‘Hello,’ he mumbled.

‘Where are you going, then?’

The smile vanished. ‘Gotta go get, uh, axes,’ the boy said, looking down. At his side his fingers started twitching, forming and re-forming fists. ‘Clearing – um . . . don’t know—’

Helga placed her hand gently on Volund’s shoulder. ‘It’s all right.’

The boy’s lower lip quivered. ‘Don’t know,’ he repeated plaintively.

‘I know where you need to go,’ Helga said.

Volund looked up at her, shyly scanning her face. ‘You . . . do?’

The smile came easy to her. ‘I do. Follow me!’ She pushed past the boy and ducked down the side path, and moments later, she emerged into the clearing, Volund hot on her heels.

‘There!’ Volund shouted behind her and ran towards the discarded axes, beaming as he scooped them up. ‘I found them!’

‘Yes, you did,’ Helga said, watching the blades resting a hand’s width away from his grinning face. ‘You’re right. Now, let’s be careful, shall we?’

Volund nodded, gazing at Helga. ‘You saved me,’ he said.

After gently rearranging the axes in the boy’s arms to decrease the likelihood of severed limbs, Helga led him like an ox to a large pile of branches. ‘What do you mean?’

‘I didn’t know where to go, and Father gets angry when I don’t know where to go.’ Volund blinked. His shoulders tensed, his brow furrowed and suddenly the boy looked more like a man. ‘You’re stupid, boy,’ he growled, sounding exactly like Bjorn. ‘I’d break your head open if I thought there was anything there that could escape.’ His grip on the axes tightened. ‘Get out. GET OUT!’ Then he looked at Helga and something went slack in him. His usual innocent cow-face was back. ‘And then Mother will say, “Please, Bjorn – leave him! Leave him be, he’s just a babe!” and then Father will say, “He’s nothing but a lump and it would be better if he didn’t exist.” But I found the axes and now it’s all right.’

Almost outside her body, Helga looked down on her arms. Despite the lingering evening heat, the hairs stood on end. She tried to imagine Bjorn drunk, hemmed in by walls, furious at his idiot son, with Thyri hovering behind him like a worried mother duck – and Volund, unable to grasp what was happening, unable to do anything, just . . . there.

‘You’re right,’ she said, her voice catching in her throat, ‘everything is all right. And everything will be all right from now on.’ She put as much conviction into the last sentence as she could, though she still didn’t quite believe herself.

The rune-stone felt heavy at her breast.

*

Thyri and Agla had taken up stations at the workbenches near Hildigunnur, who was directing the work with her usual quick gestures and quiet commands. Jorunn was sitting in the

corner, talking to her father. Sigmar, Karl and Bjorn were nowhere to be seen.

‘Just go and sit quietly over in your spot,’ Helga whispered to Volund. ‘I’ll bring you some things.’ The boy looked at her, eyes wide, and nodded. She watched him shuffle over to the children’s play area, large and ungainly, nothing but a bull calf. It took her no time at all to find the bones the kids had been playing with last night, and when she brought them over to Volund, he touched them reverently before looking around for confirmation that he was indeed alone with the toy hoard and wouldn’t have to share.

He immediately sank into some strange, incomprehensible game of his own devising.

‘. . . but that is no excuse,’ Agla said from the workbench, voice raised. Curious, Helga drifted closer.

‘I don’t know,’ Thyri said. ‘There are different situations.’

‘I don’t care. If you’ve promised yourself to a woman, you stay promised to her.’ The knife in her hand hit the carving board with a series of sharp noises, like a woodpecker in a tree.

‘You’re absolutely right,’ Hildigunnur said in a soothing voice. ‘Men shouldn’t go sniffing where they have no business. But even the best behaved sheep will stray if the gate is open and the dog is sleeping, won’t they?’

Helga watched Agla’s face as Hildigunnur’s imagery battled with her emotions. ‘Still no excuse,’ she muttered. ‘But I see your point.’

‘Bah – they’re good for nothing,’ Thyri said with forced cheer.

Helga watched as her mother pounced on the opportunity. ‘I’d say they’re good for one thing, at least,’ she added, drawing chuckles from the women. And then, Helga thought, waiting – yes, there it was: the indrawn breath, the serious voice. ‘All women should know’ – Agla and Thyri leaned in – ‘that men are like bridges.’ Confusion on their faces; Hildigunnur had them in the palm of their hand.

‘Lay ’em right the first time and you can walk over ’em for the rest of your life.’

The gales of laughter bounced around the longhouse. Even Helga found herself smirking through reddened cheeks.

‘Will you hens keep it down! We’re trying to have a conversation in the same valley,’ Unnthor shouted from the far end.

‘Of course – anything you say, Husband,’ Hildigunnur said sweetly, batting her eyelashes across the room to another burst of laughter. When she turned around to continue work, Agla and Thyri did so as well, only now they had real smiles on their faces. When both women were engaged in their work, the old woman in the middle looked over her shoulder at Helga, caught her eye and gave her a look that said, That’s how you do it.

Helga smiled back. I saw. I understand.

Behind her she could hear the door opening. Gytha stepped in, scanning the room before walking over to her bed.

Without turning, Agla asked, ‘Who’s watching the children?’

‘Runa,’ Gytha replied. ‘And I figured why not? They’re her kids.’

‘So young, yet so wise,’ Hildigunnur said, smiling.

‘Yes,’ Agla said, ‘there’s nothing that one can’t puzzle out.’ Hildigunnur rewarded her with a smile, and she grinned.

‘Helga – come over here,’ Unnthor rumbled. ‘Don’t spend your time in the hen-house.’

‘What does that make you, Husband?’ Hildigunnur shouted across the room, and giggles again turned to laughter as Agla and Thyri exchanged grins. Helga drifted across and perched on a bench a safe distance from Jorunn. The slim woman smiled at her, but it didn’t reach the eyes.

‘Settle one thing for us, child,’ Unnthor said. ‘Why does your mother always win at Tafl? Jorunn says it is because she thinks ahead. I say it is because she is a witch.’

‘Both,’ Helga said without thinking.

‘I heard that!’ The mock outrage in Hildigunnur’s voice cut through the hall.

Jorunn smirked. ‘So what does that make us?’

‘Lucky?’ Helga said. ‘We’re still alive.’

Jorunn’s smirk grew to a smile as she moved closer to Helga. ‘She’s either a wise head or a smart-arse, this one,’ she said. ‘Either way, I like her.’

Unnthor gave Helga a smile of his own. ‘You’re one of mine, I reckon,’ he said. ‘Even though we did get you for free, sort of.’

‘And of course, if you go after our inheritance we’ll kill you,’ Jorunn said.

A bubble of nervous laughter burst out of Helga. ‘Of course,’ she said.

‘Leave the child alone, Daughter! There’ll be no inheritance for another forty years. My dear witch-wife will keep me alive for some time yet. I remember one time when—’

Helga’s focus was broken by a light touch on her arm: Gytha stood by her side, looking flustered.

‘Can we . . . ?’ she mumbled, glancing at the door.

Helga rose. Out of the corner of her eye she caught Jorunn looking at her father with a fixed grin. ‘Come on. Outside,’ she said.

*

The sky was a dark blue dotted with the dull white of clouds drifting overhead, and Helga shivered. Night-time had a way of bringing out the cold, and sitting in the warmth and listening to Unnthor ramble on suddenly felt a lot more appealing. She turned to Gytha and was about to snap at her when she remembered what Hildigunnur had just taught her about being gentle and patient. Instead, she asked softly, ‘What’s the matter?’

‘It’s Runa,’ Gytha said. ‘She was acting really strangely – down by the river.’

‘Isn’t that just what she always does? She’s spiky, that one.’

‘Well, yes, but it wasn’t like that,’ Gytha said. ‘She was almost – well, quiet – but not in a good way.’

‘Oh?’ Helga was fighting to keep calm. Knives. Knives in the dark . . . The sensation was like intense hunger scraping at her insides. She managed to keep her voice level. ‘Tell me more.’

Gytha looked at her feet. ‘I don’t know that there is more to tell. It was just . . . She came to us from upriver, kind of just stomping through the grass, then when she saw me she seemed to . . . well, reel something in within herself – and then she sort of nodded, as if I should just go, you know? She really meant it, and I felt . . . well . . .’

‘Runa doesn’t strike me as the sort of person who holds too closely on to something that’s angered her,’ Helga pointed out, and Gytha snorted.

‘Somewhere up north there’s a lair with no she-bear in it,’ she said.

Helga smiled, but she couldn’t shake that growing feeling of unease. ‘I’m sure if there’s something bothering her we’ll find out soon enough.’

‘So do you think we should talk to her?’

‘Us?’ Helga thought about it for a few moments, wondering if she really should go and find out what was up, but the thought of speaking to Aslak’s wife didn’t appeal, even when she wasn’t furious. She shook her head decisively. ‘No . . . no, it’s probably nothing. At Riverside, if something needs sorting, my mother will get to it. But you did the right thing, telling me. Come on, let’s go back inside.’ She opened the door and all but pushed Gytha in.

Above, darkness bled into the summer sky.

*

It hadn’t taken Einar long to set up the big table. Einar’d told her Jaki had made two or three before he got it right, but this one was perfect: a really clever build that was just as easy to dismantle as to slot back together. When it was just the five of them it spent most of its time tucked away along one side of the longhouse, but now her parents’ table was once again a place of laughter and nourishment, laden with platters and bowls heaped full of food from farm, forest and river.

‘Eat, children,’ Hildigunnur said, and barely a moment later, Bjorn’s knife point was buried in a nice fatty joint of mutton half submerged in rich broth.

‘Had my eye on this one since we sat down,’ he crowed triumphantly.

‘Lamb’s nice too,’ Karl said. Helga looked up and found him staring at her. ‘Young and tender.’

‘Better than old goat,’ Jorunn said pointedly, and Karl glared at her as laughter bounced around the table. Sigmar, sitting next to his wife, was quietly and efficiently stacking his plate with as many vegetables as meat.

Gytha stared at the Swedish man with undisguised disgust. ‘Why are you eating so much crap?’ she said.

‘What do you mean by that?’ He smiled at his niece. ‘There is no crap on my plate.’

She pointed. ‘Roots? Leaves? What are you – a rabbit?’

Agla reached over, scowling, and grabbed her daughter’s arm, but Sigmar flashed her a grin before putting on a serious face. ‘Yes – on my father’s side. Well, I assume so, at least.’

‘Why?’ Gytha said.

Out of the corner of her eye, Helga could see Hildigunnur smirk.

‘Because whenever I was just about to fall asleep as a boy, my mother would call my father and tell him to come and do her like a rabbit,’ Sigmar said, smiling sweetly.

A moment, and then—

‘Oho!’ Bjorn said, roaring with laughter as Gytha turned crimson. Jorunn elbowed her husband, but the grin on her face suggested she might not be utterly outraged.

Helga glanced down towards the end of the table where the youngest of the brothers was sitting, head bowed and hands folded in his lap. Next to him, Runa was looking like a thundercloud, lips pursed, brow furrowed. She muttered something to Aslak, who looked at his hands and nodded.

The sound of Unnthor’s mug slamming down on the table silenced them all – the father of the house still had that ability. He frowned, drew the noise around him into himself, and looked commanding. ‘You children! You are all awful and horrible—’

‘—which clearly means you must be ours,’ Hildigunnur finished, her eyes sparkling.

Unnthor turned to his oldest son. ‘And now we’re all here together. It won’t happen again for too long a time. Tell the family how you’re living,’ he said. ‘Give us your news.’

For once the dark-haired man looked less than confident. ‘We – we live well,’ he started, and Agla, beside him, beamed. ‘We have a big farm just inland from the sands.’

Kin (Helga Finnsdottir)

Kin (Helga Finnsdottir)