- Home

- Kristjansson, Snorri

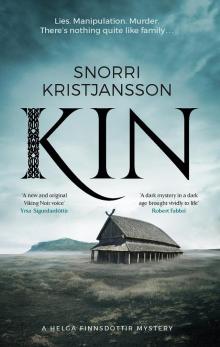

Kin (Helga Finnsdottir)

Kin (Helga Finnsdottir) Read online

Kin

Also By

Also by Snorri Kristjansson

The Valhalla Saga

Swords of Good Men

Blood Will Follow

Path of Gods

Title

Helga Finnsdottir Book 1

Copyright

This ebook edition first published in 2018 by

Jo Fletcher Books

an imprint of

Quercus Publishing Ltd

Carmelite House

50 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DZ

An Hachette UK company

Copyright © 2018 Snorri Kristjansson

The moral right of Snorri Kristjansson to be

identified as the author of this work has been

asserted in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication

may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any

information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library.

EPUB ISBN 978 1 78429 808 1

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters,

businesses, organisations, places and events are

either the product of the author’s imagination

or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to

actual persons, living or dead, events or

locales is entirely coincidental.

EPUB by CC Book Production

Cover design © 2018 by Ghost

www.quercusbooks.co.uk

Dedication

To Morag, who taught me to appreciate murder mysteries.

Family Tree

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Acknowledgements

Chapter 1

Karl

She dipped her hand in the barrel of ice-cold water and held it down, watching the hairs rise on her forearm. Her fingertips tingled, then the stinging faded away until her hand felt like it was just meat, throbbing in the enveloping, relentless cold – but she held it still, forcing herself to form a bowl as slowly as she could. Drawing a deep breath, she looked at her fractured reflection. A young woman stared back at her, eyes narrowed in determination, high cheekbones and a set jaw forming the impression of a descending bird of prey.

‘Helga!’

She exhaled and splashed her face with the cold water. ‘Coming!’

When she rounded the corner of the barn the land opened up around her. She could see over and through the treetops, all the way down to the longhouse by the river. The old barn was just visible, but the other houses were all hidden by the trees. Following the river she watched the Ren Valley open up, the dark browns and rich greens of forest giving way to patches of painstakingly cleared land. Late one night, when the ale had settled in him, her father had said that he was the ruler of all he could see. Some might have argued that the valley wasn’t his by any rights, but she had yet to meet anyone who saw Unnthor Reginsson sitting in his high seat with axe and bow within reach and wanted to argue.

‘Are you done?’ Einar’s voice rang out. She could picture him, down by the foot of the hill, standing by the side gate. Even at twenty-five winters, he still had the face of a boy. She knew he must have changed since the day she first came to the farm to stay with Unnthor and Hildigunnur, eleven winters ago, but it didn’t feel like it. She remembered watching him run past, chasing Unnthor’s daughter and trying to splash water on her. Even though she’d not seen him chase girls since Jorunn left to be married, he’d always be that boy to her. She smiled to herself.

‘Yes,’ she shouted back. The hay was stacked where it needed to be and a path had been cleared for the sheep. They’d be going on round-up in a month or so, but the longer they left it, the messier it got. Deal with things quickly and effectively. Her mother had taught her that.

She skipped down the path from the new barn, drinking in the air while it still held a bit of the night’s cold. The thick trunks towered over her. In the winter they shielded her from the winds coming up the valley from the southeast; now they gave her a nice bit of shade from the morning sun. As the ground levelled, she could see her foster-brother below, moving towards the gate.

‘Don’t you dare check my work, Einar Jakason,’ she muttered under her breath, and he must have heard her because he stopped and just watched her, waiting patiently. Thinking of something funny to say, probably. Helga smiled. He regularly tried to get one over on her in their war of words, but so far he’d been unsuccessful. She might not be Hildigunnur’s daughter by blood, but she was a quick learner and she’d caught plenty enough of her adoptive mother’s sharp tongue.

When she cleared the trees, Einar was still there waiting, a coil of rope around his shoulder. ‘What took you so long? Were you snacking on the hay?’

‘Girls don’t eat hay, Einar,’ she shot back. ‘Which means whoever’s saying she’s your girl these days is probably a horse.’

As soon as she came close enough, he swatted at her with the rope. ‘You’re a witch,’ he said.

‘Am not,’ Helga said. ‘If I was I’d have turned you into something passably attractive.’

‘Pff,’ Einar said, grinning.

His father Jaki, broad-shouldered and silver-haired, stepped out of the longhouse and shouted, ‘Get a move on, you two – they’re all coming today!’

Einar rolled his eyes. ‘Yes, Father,’ he shouted back, then he turned to Helga. ‘Come on, we need to sort out the old cowshed.’

‘Why?’ Helga asked, not moving.

‘Apparently Bjorn and his lot are staying there.’

‘Is this to keep the brothers separated?’

‘It is,’ Einar said. ‘Why d’you think the big man went east while Karl went south? Apparently they used to fight every single day – Karl beat up his brothers again and again, until Bjorn got strong enough to stop him. Hildigunnur got a lot better at healing wounds that year.’

‘We’re in for a great time, aren’t we?’ She sighed.

Einar shrugged and pushed off the fence. ‘It’ll be all right,’ he said as he walked off. ‘I’m sure the old ’uns’ll keep them reined in.’

*

The inside of the old cowshed smelled faintly of animals and stale hay. Sunshine seeped in through cracks in the wall where the wood had warped, but most of the space was draped in a pale light somewhere between dusk and shadow, except for a bright cone spreading from the open door which showed the skeleton of a once-functional building littered with an assortment of tools, lumber and broken farm-stuff. A stack of planks the height of a man sat in one corner, next to some broken rods and unfinished hides strung on warped old frames. A solid rune-covered stone pillar stood in another corner, nearly hidden in the shadows.

‘They only had four cows back then . . . Hildigunnur’s been on at Unnthor to do something about it for years, but there’re always more important jobs that need seeing to,’ Einar said. ‘They can’t make up their mind whether to tear it down or turn it into something else.’

‘I don’t know if I’ve ever been in here,’ Helga said, looking around curiously. ‘The smithy’s your father’s den, and this has always felt like it belongs to Unnthor.’ She kicked a piece of wood and it bounced into a corner. ‘So what do we need to do?’

‘First thing is to carry all of this out, I think – we need to clear the floor so we can build beds for Bjorn and his family—’

‘What? Why—?’ Helga was looking distinctly unimpressed.

‘The stories are mostly true, you know. He stopped fitting in any of the bunks in his twelfth winter. And young Volund is his father’s son.’ Einar thought for a moment. ‘Oh, right – you’ve never met them, have you?’

‘No,’ Helga said, ‘I’ve never met Bjorn, or Karl. I think they were all supposed to come five years ago—’

‘—but Karl was away and Bjorn’s family was ill. I remember. You know Aslak, of course.’

‘How could I forget? He brought two small children and a dragon of a woman with him. Will she be coming as well?’

‘’fraid so,’ Einar said.

Helga shuddered. ‘I’d rather deal with an angry bear.’

‘I know what you mean,’ Einar said.

‘And then there’s Jorunn and Sigmar. I remember her, I think, but I haven’t met him.’

‘No,’ Einar said, busying himself with a cracked beam, suddenly less interested in talking.

Helga grabbed a spade with a broken handle. ‘I don’t remember having seen this one.’

‘They’re all old things,’ Einar said, shifting a plough with one handle out of the way. ‘Unnthor’s been meaning to repair ’em for a while now, but d’you know what I think?’

‘You think?’ Helga said, feigning surprise.

‘Shut your mouth,’ Einar said over his shoulder, lumping the old plough towards the door. When he came back he was practically twinkling with mischief. ‘I think the old man is so happy at how the farm is going that he allows himself to own broken tools – so he just leaves ’em where they break and Father drops ’em in here.’ He looked around at the debris. ‘The hoard of a brave warrior, this.’

‘Hah,’ Helga said, ‘I find that hard to believe.’ She thought of Unnthor, her adoptive father, who’d taken her on eleven winters ago – at his wife’s urging – just as the farm was emptying of children. Picturing him being easy with his hard-earned riches was almost impossible. Back in the day there’d been rumours that he’d come back from his raiding in the west with a hoard to equal anyone’s, but the old bear always flat-out denied it. With the ever-present Jaki’s help, he’d sent back most of those chancers who’d come to look. The rest were buried just beyond the fence to the west. Eventually word had got out and the locals, seeing how hard Unnthor worked his farm, reasoned all those rumours were just that, fireside stories, and soon enough those in search of quick and easy profits found other places to look.

‘I find that hard to believe,’ Helga repeated, then added with a smirk, ‘Hildigunnur wouldn’t let him!’

‘Maybe,’ Einar said, ‘but she’s kept the old bear company for so long . . . I reckon she knows when to fight and when to look the other way. They’re each as stubborn as the other, those two.’

‘Probably why they’ve stayed married,’ Helga said, shifting a couple of broken sledgehammers. ‘In time my mother’s story will feature “The Legend of the Taming of Unnthor”.’

‘It’ll be a good story, though. Just like Unnthor has “The Wooing of Hildigunnur”. I still like it, even though I’ve heard it at least once for every summer of my life.’

‘So in your case that’d make – what, twelve?’

Einar made a face at her and bent to find the grip on a big cracked whetstone. ‘Unnthor Reginsson went to find himself a wife. He wanted Hildigunnur but her father, old Heidrek, was part troll . . .’

Helga strained to shift a stack of planks out of the way. ‘Only part? The old men can’t have been far into their drink when they told you last time. I thought he was—’

‘Nine feet tall if he was an inch. And the bastard filed his teeth,’ a gruff voice said from the doorway: Unnthor of Riverside, chieftain of Ren Valley and ruler of all that he saw, blocked out most of the light. His shoulders weren’t that far from touching either side of the doorframe, his grey hair was still thick enough to plait and his neatly trimmed beard was full. At sixty-two summers he still struck an imposing figure. ‘He used to kill bears for fun, that one.’

‘And you strode up to him,’ Helga said.

‘And smacked him in the head with the thigh-bone of an ox,’ Einar said.

‘Not quite,’ the old man said. ‘I opened my mouth to speak, and he hit me – knocked me back four steps and cracked my jaw good and proper. Then I hit him with the bone, and down he went. When he came to I asked him if he gave me his permission to marry his daughter.’ He joined them in shifting tools towards the door.

Einar smiled. ‘And he said—’

‘—the crusty old troll laughed and said, “Go right ahead. She hits harder than I do.” And he wasn’t wrong,’ Unnthor said. ‘No – leave that.’

Einar stopped just short of touching the stone pillar. ‘Why?’

‘It would be bad luck to move it. It’s been there since the day we settled. The gods would disapprove,’ he added. ‘Just leave it.’ Einar shrugged and moved towards the pile of timber. ‘I need you to get started on the beds for Bjorn and Thyri – oh, and little Volund as well,’ Unnthor said. ‘Stack the planks over there,’ he added, pointing at the corner of the cowshed furthest from the door.

‘Little Volund is now twelve winters,’ Helga said, ‘and he hasn’t been little for a while, Mother says.’

Unnthor dismissed her with a huff and a hand-wave. ‘He’s little if I say he is,’ he said. ‘Einar, go and get your father’s tools. We’ll build the beds where you’re standing.’

Einar nodded, dropped the planks on the ground and left. The rest of the debris of farm life that had been tucked away in the old cowshed was now neatly piled up outside by the fence and the empty space was filled with silence.

‘My own flesh and blood is coming for me, Helga,’ Unnthor said quietly.

‘What do you mean, Father?’

The old man turned to look at her. In the half-light he seemed very tired. ‘My own flesh and blood,’ he said, ‘with darkness in their hearts. I saw it in a dream.’

She opened her mouth to speak, but the rattle of metal on metal warned of Einar’s approach. Unnthor heard it too, and in a blink the tired old man had disappeared, replaced with the fearsome chieftain.

Despite the heat, the hairs on Helga’s arms rose.

*

At noon, Jaki’s voice boomed across the grounds: ‘Riders!’

Helga felt a surge within. Unnthor’s odd behaviour in the shed had stuck with her, but she did her best to ignore it. Something’s going to happen. While the safety of the everyday was comforting, there was a pull to this: the world was coming her way. She ran to the main gate, where there was an unhindered view down the valley. Jaki and Einar were already there.

‘They’re not sparing the horses,’ Jaki pointed out.

‘When did Karl ever spare anything?’ Einar said.

The stocky man grabbed his son by the arm, none too gently. ‘You will watch your mouth,’ he growled. ‘Do you understand?’

‘Yes, Father,’ Einar said, trying not to wince at the grip.

Jaki let go. ‘Just – if you can, say nothing.’ He glanced at Helga. ‘That goes for you too, girl

,’ he said.

Helga nodded. ‘Of course.’ She stared down at the riders. She could just about make out the shapes . . . ‘Are there three of them?’

‘Too far for me to tell,’ the old man mumbled.

‘Maybe . . .’ Einar looked puzzled. ‘But who have they left behind, then?’

Froma distance, Hildigunnur’s voice rang out across the yard. ‘Helga? A little help—’

With a last look at the approaching riders, Helga turned and ran towards the longhouse, an imposing structure with walls almost twice the height of a man. The woman in the back doorway looked like a twig in comparison, but Helga had quickly learned not to judge her by her size. Hildigunnur, the woman who’d become her mother, was tougher than most men. She might not be either tall or wide, but she moved with an ease that belied her fifty-five summers, and she could still run for half a day without stopping. As impossible as it might seem, she was Unnthor’s match in all ways. For the last thirty years they’d been at the heart of their valley, and the next over, and the one after that. Women travelled for days to seek Hildigunnur’s advice; most thought her firm but fair – and those who didn’t at least had sense enough to keep silent and tell stories about witchcraft when they were well out of earshot. Like her or not, everyone agreed that her wisdom ran deep.

‘Shift it, girl,’ she shouted. ‘I’ll grow a beard waiting for you.’

‘And if you did, Mother, it would look great.’

‘Flattery will get you nothing but trouble,’ Hildigunnur said, smiling. ‘Pots await. The travellers will need feeding. So you’ve been building beds – is that all done?’

‘A while ago,’ Helga said. ‘Einar was pretty quick.’

‘Oh, he’s a good ’un,’ Hildigunnur said. A glint flashed in her eye. ‘And not bad to look at, either.’

‘Mother!’ Helga said. ‘Ugh! Really?’

‘You may see him as a brother,’ Hildigunnur said, leading Helga into the longhouse, ‘but people see things differently.’ She glanced over her shoulder before she closed the door. Unnthor had joined Jaki and Einar at the gate.

Kin (Helga Finnsdottir)

Kin (Helga Finnsdottir)