- Home

- Kristjansson, Snorri

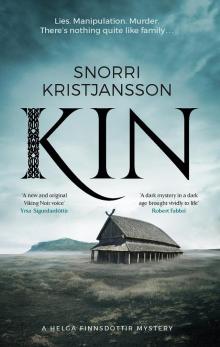

Kin (Helga Finnsdottir) Page 14

Kin (Helga Finnsdottir) Read online

Page 14

The image crashed into her mind so hard that her knees buckled.

The pendant.

The bloody pendant.

When he was fighting with Bjorn, he’d tucked something in under his shirt. The light had caught on it when he was insisting on helping her put away the crockery. It was silver, a Hammer of Thor.

Helga staggered towards the door, suddenly struggling to breathe. This felt important.

Outside, the body lay in repose, now covered with one of Hildigunnur’s cloths. The mastiff sat by his side, head hung low, looking miserable. Behind her, Helga could hear voices – Bjorn and Jorunn? – coming from the woodshed. She had to check, but quickly.

When she knelt by the body, the dog’s head snapped up and it growled half-heartedly at her.

‘Ssh,’ she whispered. ‘It’s all right.’ Quickly, she pulled the cloth away to reveal Karl’s pale face, his neck – and nothing.

‘What are you doing?’ Hildigunnur was standing behind her.

Helga froze. ‘I— Um—’ She looked over her shoulder, narrowing her eyes to keep out the sun. ‘I needed to check.’

‘Why?’

‘Because he had a pendant. And now it’s not there.’

The sun at Hildigunnur’s back turned her mother into a dark silhouette. ‘I see.’ Then, ‘Get up, quick. They’re coming.’

Helga rose, feeling uneasy. Had she discovered something important? Had she done something wrong? But her mother gave nothing away, communicated nothing. How does she even feel about this? Helga realised that she didn’t know. Her mother had been shocked, then angry . . . but why? At the moment she thought it just as likely that Hildigunnur was angry at Karl for having the gall to die on the farm without permission. Looking out past the gate, she saw Aslak and Runa approaching. Even from a hundred yards away, she could see that whatever was between them was even worse than it had been.

‘You could break rocks with those shoulders, they’re set so hard,’ her mother muttered under her breath as she glanced Runa’s way.

Helga had to stifle a laugh that was part amusement at the precision of the observation and part relief that her mother was her old self again. ‘How’s Agla?’

‘She was always fragile, but I think she’ll recover.’ Hildigunnur said no more, for Aslak and Runa were nearly within hearing range.

They joined them in a circle around the body, and the silence grew with each new member of the family, like snow on a roof, until Helga felt her chest squeezing. Nobody said anything; nobody looked anywhere but at the ground.

Only when they were all gathered did Unnthor appear, with Jaki and Einar at either side.

‘We have marked out the site,’ he growled. ‘The necessary preparations have been made. The gods are not pleased about this.’

The gods are rarely pleased about anything, Helga thought, but she kept that to herself. Unnthor turned and stalked away, and like a flock of sheep they followed. No one talked, no one looked at anything but the broad back of the Farmer at Riverside. Without words, Jaki and Einar broke away and walked towards the shed to collect shovels and picks. A quick barked command and Bjorn swung by the woodshed, returning with an armful of lumber.

Helga found herself walking next to Gytha. Her face was still pale, and she looked tired and worn. A moment of doubt – of fear, even – then Hildigunnur’s voice echoed in her head: Don’t be stupid, girl. You know what to do. She reached out and put her arm around Gytha’s slim shoulders. A captive breath escaped the girl’s throat in a sob, then she was shuddering and clinging to Helga, holding her shirt in a death-grip. They walked awkwardly together at the back of the line of people, Helga muttering soothing words to the shaking girl. She looked at the backs of her family, heads bowed, all shuffling to the grave-site like lambs to slaughter. Almost without thinking, she touched the rune on the thong around her neck.

Images flashed before her eyes: the twinkling smile of the old man in the field. His whispered words, his voice stronger than his age suggested. The rune of Nauth, the wind hissed at her. It will tell you about the wants, wishes and needs that flow in you all.

‘Worth a try,’ Helga muttered.

‘What?’ Gytha sounded like someone half asleep.

‘Nothing,’ Helga said, ‘nothing at all. Look,’ she added, pointing ahead. ‘We’re nearly there.’

Chapter 11

Guilty

Helga sat in the midst of her extended family, but she felt utterly alone. Around her, shovels cut rhythmically into the ground, slicing the turf – like a blade through skin. She took a deep breath and tried to remember how the smell of grass used to make her happy. She wanted to let her mind drift, lulled by the repetitive motions, but in the company of her family it was proving hard. To her left Bjorn was working at a steady pace, shoulders rising and falling with shovel-strokes that could easily lop the head off a man, shifting heaps of soil up onto the bank, out of the growing shape of the longship. Sitting by the side, Runa and Thyri busied themselves weaving bark into panels and shapes to furnish the grave. The whole family was working around her to create Karl’s final resting place. Whenever a task finished, Hildigunnur was there to snap out new orders. She never raised her voice, but there was not a moment’s respite anywhere.

‘Get to it, Helga. Come on.’

She blinked at her mother’s voice and resumed spinning the ropes. They felt rough in her hands. Helga imagined what they would look like lashed around bent and curved branches, holding together a cage clad with bark to form a shell just like Hildigunnur had described. She pictured it, upside down over Karl’s body as it lay on the deck of the boat, protecting him from the soil raining down from above, getting him ready to sail to the world of the dead. As he hadn’t died in battle he wouldn’t go to Valhalla, but Unnthor had decided that his son should be buried like a rich man and a landowner, in the field of prayer, within sight of the stone table and the oak, so that was that. Helga stole a glance over at them and shuddered. She had only seen her father preside over a handful of ceremonies, but even he looked oddly powerless and human standing next to the stone and the oak. Even now, on a pleasant summer afternoon, they radiated menace like ill-tempered bulls.

The gods don’t care about us. Looking at the tree, she was filled with a terrifying certainty. We are summer breeze and sunlight. They are the tree and the stone.

The hole was deep enough to reach up to the middle of Bjorn’s thigh. Behind him Aslak was compressing the sides with a broad plank, strengthening the inner walls so they would withstand the waves of seas beyond this world.

The hole was taking shape and finding form before her eyes, thanks to Bjorn’s work and Aslak’s hands. As the woven panels of bark were finished, Jorunn jumped down into the grave and laid them out in the unmistakable shape of a longship. Above them all stood Unnthor, now a silent taskmaster, hand on the haft of his axe. He stared at them, unmoving and unblinking, daring any one of them to shirk their duties.

No one did.

When the sun started descending towards the horizon, the ship was ready.

It was time to lay Karl to rest.

Hildigunnur gestured silently to Bjorn and Sigmar and as the rest of the family stood looking down at their handiwork, the two men took hold of the blanket under Karl’s body and hoisted him up before walking towards the stern of the ship, where the hole was shallowest. They walked carefully along to the middle of the grave before lowering the body gently down onto the bark in the bottom of the ship.

Gytha was standing silently beside Helga as her father’s body was carefully laid out – then she caught a breath in her throat, as if trying to muffle her grief. As she started sobbing, Helga awkwardly embraced the shaking girl, and was rewarded with a bone-cracking hug.

Unnthor stepped down into the ship and stood by Karl’s head. ‘The gods will see my son for what he was,’ he rumbled, and the world fe

ll still around them. These were the words that should be spoken, and it was important that they be spoken right. Helga didn’t quite know how they’d sound if they were spoken wrong – she had always believed her father. Looking down at the man by their feet, though . . .

‘Karl was a Viking, true to his land and true to his gods. He roamed, he fought and he bent the knee to no man.’ Clenched fists and pursed lips all round. Bjorn’s massive chest rose and fell like that of an overworked horse. ‘There were few who would wish to face him when he was awake and aware. My son died a warrior; whoever killed him lives an honourless coward.’

And stands by his grave, looking down on him, Helga thought. You need some serious balls to do that. She stole a glance round: Bjorn, Sigmar and Aslak were all stony-faced. Agla stood by Hildigunnur, chin tilted upwards, lips pursed, looking like a stone sculpture. Thyri stood by her gigantic husband, hand on his arm, glancing at his face, fear in her eyes. What is she afraid of? Helga had to work to keep the frown off her face. Runa was staring intently at Jorunn, looking like she was trying to draw her eye with willpower alone. She’s moved further away from Aslak, she noted. Why? What’s happened between them?

Strange.

‘My son shall take with him the means to pay his way, wherever he’s going,’ Unnthor said. From the folds of his tunic he produced a pouch about the size of his fist and threw it down into the grave. It landed with a dull clink. It was quick, the glance that passed between Sigmar and Jorunn, but Helga saw it. ‘And he shall take with him the means to defend himself,’ Unnthor continued, and Karl’s axe followed suit. ‘And he shall take with him the means to travel where he needs.’

A horse whinnied behind them. Karl’s mare was reluctant to go down, but she was well-trained, and Einar led her into the longboat, whispering calming words in her ear as he lined her up alongside to Karl, and—

—it happened so fast that Helga almost missed it.

Unnthor’s arm moved, and suddenly the knife was in his hand, blade facing away. The swing connected with the back of the mare’s head with a dull clonk, and the horse keeled over. Einar strained, yanking the reins until the mare that Karl had so prized was lying next to him. They looked peaceful together, almost like they were asleep.

‘And he shall bring with him a faithful companion,’ Unnthor said.

Jaki followed his son down into the ship, leading Karl’s mastiff by the leash.

Helga tasted vomit in her mouth, and looked away. She knew what needed to happen, but that didn’t mean she had to like it. There was a sound like someone stepping on a twig, and when she opened her eyes the dog was lying on Karl’s other side, head twisted at an unnatural angle.

Unnthor nodded to Jaki and Sigmar, who pushed themselves up onto the bank and picked up the wooden structure they had built to house Karl on the next leg of his journey. They placed the shell over the bodies of man, horse and hound, then walked up out of the ship.

‘Get going,’ Hildigunnur said. ‘Shovels, but careful.’

As one, the family got to work. The soil piled on the banks of the hole went back down, first sprinkled on top of the wooden structure, until slowly, the bark panels disappeared from sight, sinking under the still waves of the earth. Then, gently, the wooden struts were covered, leaving a hump above the ground.

By the time the last shovelful and the last handful of soil fell on Karl’s burial mound, the sun was half gone.

They all knew it was finished. Gytha and her mother had no more tears to cry; Unnthor had no more words to say.

‘Home and food,’ Hildigunnur said pragmatically. ‘I’m not digging holes for you lot as well.’

As soon as her mother’s lips started moving, Helga’s feet did too: she needed to be in the right place at the right time. Sure enough, Hildigunnur charged ahead, her stride determined, and Helga fell in beside her mother.

‘Before you say anything,’ Hildigunnur said without looking at her, ‘you’re helping me with the pots.’

A half-strangled laugh escaped Helga’s lips. ‘I should think so,’ she said. ‘I don’t think I can outrun you yet.’

Half a step ahead, Hildigunnur’s face was almost hidden, but there was the hint of a smile. ‘You make an old woman happy, Daughter,’ she said. ‘Well, as happy as one can be on a day like this.’

‘Let’s hope Karl is happy fighting whatever he’ll meet in the afterlife,’ Helga said.

‘He’ll come back to haunt us,’ Hildigunnur said, ‘mostly because he’ll annoy everyone wherever he goes and get kicked out.’

Now it was Helga’s turn to smile. Now. It had to be now. ‘I was wondering, though – should there not be runes? To guide his way?’

Hildigunnur glanced at her. ‘What do you know about runes?’

‘Nothing,’ Helga said quickly, then corrected herself. ‘Well, I mean, I’ve heard stories . . . aren’t they magical?’

Hildigunnur snorted. ‘About as magical as my arse. Scratch a bit of wood and see what happens.’

‘Why – what can happen?’

‘If you scratch the right pattern and you know what you want, something might,’ Hildigunnur conceded. Then she smirked. ‘Maybe a big bull of a man might come to your house, hit your father with a thighbone and sweep you away to a life of joyous rutting and troublesome children.’

‘Mother!’ Helga exclaimed, to chuckles from the older woman. ‘Are you saying you bewitched . . . ?’ She gazed at her father striding along behind them, then Hildigunnur shot her a look back that very clearly said I’m not telling. There was a glint in her eye, but Helga couldn’t help but notice that her mouth was set in a serious line.

*

Back at the longhouse, an uneasy silence settled, only occasionally punctured by a muttered request or the sound of blade on wood from the corner where Hildigunnur and Thyri were manning the pots. Helga tried her best to keep up, but the two women worked with almost impossible speed, and no matter how fast she peeled roots and passed along chunks of meat, there were always hands waiting to grab from her.

‘Go and get firewood,’ Thyri finally snapped. ‘You’re slowing us down.’

Hildigunnur said nothing.

Stung, Helga made her way out past Sigmar, who was sitting next to Unnthor and speaking in hushed tones. Volund was sitting by himself, his back to the wall and his hands in his lap, looking unhappy as he glanced aimlessly around the room. The only ones not affected by the mood were Sigrun and Bragi, who were playing some complex game in the corner involving three bones and a stick.

When she opened the side door the evening breeze welcomed her, caressing her cheek and drawing her outside. She thought of the angry people inside the longhouse. It feels good to have a closed door between us. The sky stretched above her, honeyed gold in the west, purple up above and black all the way to where the gods lived. If I were a bird, Helga thought, I would be up there now, flying through the colours, fast and far, to foreign lands. ‘And getting no firewood at all,’ she added.

‘I’ll help.’

She couldn’t help it – the yelp, high-pitched and girly, escaped before she could stop it. ‘Aslak! What are you doing out here?’ she said, sharper than she’d intended.

The youngest of Unnthor’s children looked back at her from his place in the shadows, just an outline against the deep blackness. ‘I just . . . needed to step outside for a little bit. It’s like a load off the chest, it really is.’ He stepped forward and the moonlight caught on his cheekbones. His eyes are so big, Helga thought, and something changed inside her. Away from his brothers, alone and outside, Aslak looked . . . different. Thinner. Haunted, somehow. Like she’d always imagined Loki from the tales.

‘Uhm . . . thank you,’ she said, flustered, and annoyed at herself for being so. ‘Help – yes, please. You know how she gets.’

‘Oh, I do,’ Aslak said, a small smile on his lips. He moved towards

her – and Helga’s heart didn’t beat again until he was past and walking towards the woodshed. What’s wrong with you, girl? Get moving!

She hurried on after Aslak, trying to push the sad, beautiful face in the moonlight out of her mind.

*

When they got back, the table was set and everyone was seated. Eyes kept going to Karl’s place like a tongue to a tooth gap, but no one said anything. Helga half expected Runa to be shooting hateful glances in her direction, but she was curiously preoccupied, unable to take her eyes off Jorunn.

‘. . . play,’ Volund was muttering sullenly, down at the other end of the table.

‘No, you’ll eat first,’ Thyri said firmly.

The spoon slammed into the bowl and a large chunk of turnip rose to meet Volund’s mouth, disappearing in one gulp. Moments later, sounds of pain followed as the boy tried to eat and keep the boiling bit of vegetable out of his throat at the same time. ‘Nngh!’ he managed at last, spitting the mouthful back into the bowl.

Bjorn turned and glared at his wife. ‘Send the boy to his corner,’ he said.

‘He should eat, otherwise—’

‘He’s not going to eat,’ Bjorn said wearily. ‘And no one wants to see that. He eats like a pig.’

Helga glanced at Volund, but he hadn’t appeared to notice his father’s insult. Thyri thought better of protesting and waved the boy off to play. He shuffled back to his area, knelt down and stuck his head under the bed. Helga caught Bjorn glancing after him, a tired, pained expression on his face.

‘On the way here, we heard stories,’ Sigmar started.

Jorunn’s mouth pursed in response. ‘Sigmar, don’t.’

‘What? We should tell them.’

‘Tell us what?’ Unnthor growled from the top of the table. Unsettled by the menace in their grandfather’s voice, Bragi and Sigrun hurried away from the dinner table and their mother’s knee as quickly as their six-year-old legs could take them.

Kin (Helga Finnsdottir)

Kin (Helga Finnsdottir)